How to Build a Predictive Model of Your Manager (and Make Work Smoother)

Your manager can't articulate how they want to be managed, but their patterns reveal everything. Learn to observe, adapt, and make work smoother.

👋 Hi, it’s Rinaldo. Every week or two, I share actionable strategies to help you clarify your message, drive decisions, and grow your influence at work regardless of your role or title.

I’m launching a live cohort course soon to go even deeper on these topics and opening up a small beta group first. Leave your info here if you want early access to the beta.

Most people try to get better at their job by improving their own skills, learning new tools, mastering their craft, shipping faster. And sure, those things matter. But here’s what nobody tells you: a huge part of success at work is understanding your manager just as well as you understand your work.

Think about it. You can be brilliant at your job, but if you’re constantly misreading what your manager needs, presenting information in ways that don’t land, or getting blindsided by feedback you didn’t see coming, you’re operating with one hand tied behind your back.

The Problem: You’re Flying Blind

Here’s what happens when you don’t understand your manager’s patterns:

You waste time on the wrong things. You spend hours perfecting a detailed analysis, only to have your manager skim it and ask “what’s the bottom line?” Or you come with just the headline, and they pepper you with follow-up questions about methodology because they needed to see your work.

You over- or under-communicate. You think you’re being efficient by keeping updates brief, but your manager feels out of the loop and starts micromanaging. Or you’re sending daily status updates to someone who just wants to hear from you when something’s actually wrong.

You get blindsided by feedback. Your manager seemed fine in the moment, but then your performance review surfaces concerns you never saw coming. You missed the signals, the questions that meant skepticism, the silence that meant disagreement, the “let’s table this” that meant “no.”

The instinct most people have is to ask their manager directly: “How do you like to work? What do you need from me?”

And look, that’s not a bad starting point. But here’s the thing: most managers can’t actually tell you. They don’t have a clear, articulated framework for how they want to be managed up to. They just know it when they see it, or more often, when they don’t.

This is why the best operators don’t just ask. They observe and pattern match. They treat their manager like a system to understand, not a problem to solve.

The Solution: Build a Predictive Model

What is a predictive model of your manager?

It’s a mental framework for anticipating how your manager thinks, communicates, and makes decisions. It’s your internal user manual for working with them effectively.

The core principle: Assume your manager’s personality and approach is a constraint. Trying to “change” your manager is a losing battle. Instead, operate as if their traits are fixed, and adjust your behavior to get better outcomes.

This isn’t about being manipulative or inauthentic. It’s about adaptation. Your manager has patterns, in how they process information, how they make decisions, how they give feedback, how they operate day-to-day. Your job is to decode those patterns and work with them, not against them.

Why this works:

It’s based on observed behavior, not wishful thinking. You’re not guessing or hoping they’ll change. You’re documenting what actually happens.

It builds trust through reliability and predictability. When you consistently give your manager what they need, in the way they need it, they start trusting your judgment.

It turns each interaction into new data to refine your model. Every meeting, email, and feedback session is an opportunity to test your predictions and get more accurate.

It helps you earn space to work independently. The better your model, the more autonomy you gain. Your manager stops questioning your decisions because you’ve proven you understand their constraints.

The goal: Faster trust, fewer misunderstandings, more autonomy.

Let’s build your model.

Section 1: How They Process Information

This is about decoding how your manager receives and processes information. Get this wrong, and everything else falls apart. You’ll be having conversations where you think you’re being clear, but your manager is frustrated or confused and you won’t even know why.

Information Type: Quantitative ↔ Qualitative

The question: Do they want numbers and data, or stories and narratives?

Some managers are “show me the data” people. They want metrics, benchmarks, trends. They ask “what do the numbers say?” and will glaze over if you start with a story. When you bring them a recommendation, they want to see the quantitative evidence first.

Other managers think in stories and examples. They want to understand the customer’s experience, hear about what other companies did, see the qualitative context. Data alone doesn’t move them, they need to feel the problem before they’ll engage with solutions.

How to observe this:

Watch what makes their eyes light up vs. glaze over in meetings

Notice what type of evidence they cite when making their own arguments

Pay attention to what questions they ask first: “What do the numbers show?” or “Walk me through what happened”

Note: Quantitative-focused managers want hard data, metrics, and measurable evidence. Qualitative-focused managers are more persuaded by stories, case studies, and examples. When presenting, lead with the type of evidence that resonates with your manager, but have both available if possible.

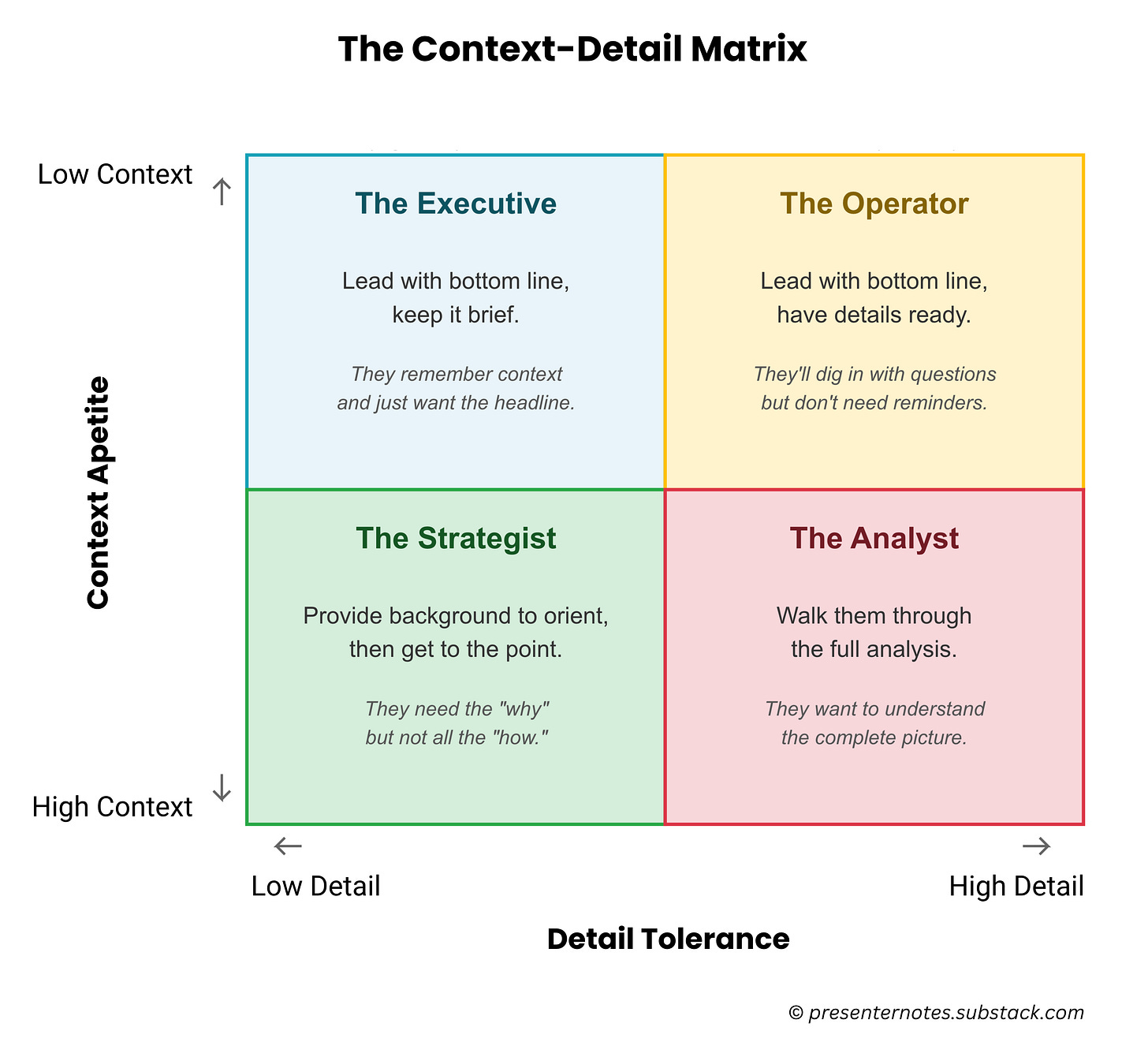

The Context-Detail Matrix

This is where most people get managing up wrong. They either drown their manager in details or leave them with too many questions. The key is understanding two independent dimensions that work together:

Context Appetite: Low context ↔ High context

The question: How much background/history do they need to understand the situation?

Low-context managers remember previous conversations. You can reference “that discussion we had about the pricing model” and they’ll know exactly what you mean. They get frustrated when you re-explain things they already know.

High-context managers need reminders. They’re juggling a lot, and they need you to re-orient them: “Remember we decided last month to test the new feature with beta users? Here’s where we are now.” Without that context, they’re lost.

Questions to help you assess:

Do they remember previous conversations, or do you need to remind them?

Do they ask “what’s the background here?” or “remind me what we decided last time?”

Can you reference past discussions without re-explaining them?

Detail Tolerance: High-level ↔ Granular

The question: Once they understand the context, how deep into the specifics do they want to go?

High-level managers trust your analysis. They want the executive summary. If you start explaining your methodology or walking through the spreadsheet, they’ll cut you off: “I trust you did the work, just tell me what you found.”

Granular managers want to see how you got there. They ask follow-up questions about your approach. They want to look at the data themselves. They lean in when you go deep, not check out.

Questions to help you assess:

Do they trust your analysis, or want to see the data themselves?

Do they ask follow-up questions about methodology and specifics?

Do their eyes glaze over when you go deep, or do they lean in?

Using the Context-Detail Matrix

Here’s where it gets powerful. These two dimensions create four distinct communication styles:

The Executive (Low Context + Low Detail): Lead with bottom line, keep it brief. They remember context and just want the headline.

The Operator (Low Context + High Detail): Lead with bottom line, have details ready for questions. They’ll dig in with questions but don’t need reminders.

The Strategist (high Context + Low Detail): Provide background to orient them, then get to the point. They need the “why” but not all the “how.”

The Analyst (High Context + High Detail): Walk them through the full analysis. They want to understand the complete picture and methodology.

Example: The Executive (Low Context + Low Detail)

Bad approach: “So last quarter we discussed the customer churn issue, and we looked at three different solutions. I analyzed the data using cohort analysis and segmented by industry and company size. When I looked at the regression...”

Good approach: “Recommendation: We should prioritize the onboarding improvements. Data shows it’ll reduce churn by 15%. Happy to dive into methodology if you want details.”

Example: The Analyst (High Context + High Detail)

Bad approach: “We should change the pricing model.”

Good approach: “Quick context: remember we’ve been seeing churn in the mid-market segment since Q3. I analyzed our win/loss data over the past 6 months and found that 68% of losses cited pricing as a factor. Here’s the data breakdown...” [walks through full analysis]

The key insight: Most communication problems aren’t about what you’re saying, but about how much you’re saying and in what order. The Context-Detail Matrix helps you calibrate both.

Processing Time: Decide live ↔ Need time to think

The question: Can your manager make decisions on the spot, or do they need time to process information before deciding?

Some managers are “let’s decide right now” people. You bring them a problem, talk it through, and they make a call by the end of the meeting. They’re comfortable with fast decisions and course-correcting later if needed.

Other managers need time to think. Even for decisions that seem straightforward, they’ll say “let me sleep on it” or “I want to think through the implications.” If you push for an immediate answer, you’ll either get a “no” or a decision they’ll second-guess later.

Important nuance: This often varies by decision size. Your manager might decide tactical things live but need 24-48 hours for strategic calls. Pay attention to where the threshold is.

How to work with this:

Fast deciders: Come prepared to decide. Anticipate their questions. Have your recommendation ready. Don’t leave the meeting without clarity on next steps.

Slow processors: Send materials ahead of time. Frame meetings as “I want to walk you through this today, then let’s decide in our next 1-on-1.” Don’t be surprised if they want to revisit decisions—it’s part of their process.

Section 2: How They Make Decisions

Understanding how your manager processes information is foundational. But if you want to influence outcomes, get buy-in for your ideas, secure resources, change directions, you need to understand how they make decisions.

This is the difference between having smooth conversations and actually moving the needle.

Decision Drivers

Primary Optimization Target(s)

The question: What outcomes does your manager optimize for?

Most managers have 2-3 primary drivers that trump everything else. When there’s a tradeoff between speed and quality, which wins? When customer needs conflict with team capacity, what gets prioritized?

Common drivers:

Speed to market - “Ship it now, iterate later”

Customer satisfaction - “What’s best for the customer?”

Revenue/business metrics - “What’s the ROI?”

Risk mitigation - “What could go wrong?”

Team happiness/capacity - “Is the team sustainable?”

Quality/craft - “Is this something we’re proud of?”

Strategic positioning - “Does this set us up for the future?”

Why this matters: When you understand what your manager optimizes for, you can frame your proposals in their language.

Example: If your manager optimizes for speed, don’t lead with “This will take 3 months but the quality will be amazing.” Lead with “We can ship v1 in 3 weeks, then iterate.”

If your manager optimizes for risk mitigation, don’t gloss over what could go wrong. Lead with “Here are the three risks I’ve identified and how we’re addressing each one.”

How to identify this: Listen to what they emphasize in meetings. Notice what triggers pushback. Pay attention to the tradeoffs they make when they’re stressed.

Recurring Questions They Ask

This is one of the most powerful observation tools in your toolkit.

Your manager asks the same questions over and over because those questions reveal their mental checklist. They’re showing you exactly what information they need to feel confident making a decision.

Track these religiously.

Common patterns:

”What’s the customer impact?” → They need to understand the user benefit

”When can we ship this?” → They’re optimizing for speed

”What’s the simplest version?” → They value shipping over perfection

”Who else needs to weigh in?” → They value stakeholder alignment

”What could go wrong?” → They need risk mitigation

”What do the numbers say?” → They need quantitative proof

”Have we done this before?” → They want precedent/proof

”How does this tie to our strategy?” → They need strategic alignment

Once you know the recurring questions, you can proactively answer them before they’re asked. This is how you build trust. Your manager starts thinking “they really get it” because you’re consistently addressing their concerns without being prompted.

How They Present Their Own Ideas

This is an underutilized observation technique.

Pay close attention to how your manager structures their own proposals, updates, or recommendations. They’re showing you exactly what they value.

Do they:

Start with the problem or the solution?

Lead with data or with strategy?

Walk through their reasoning or jump to the recommendation?

Show options or come with a clear point of view?

Frame things as opportunities or risks?

Example: Your manager always starts team updates with “Here’s the problem we’re solving” before diving into solutions. That tells you: problem-framing matters. When you bring them ideas, start with the problem.

Your manager presents their quarterly plans as “Here’s my recommendation, and here are the two alternatives I considered.” That tells you: they value showing they’ve thought through options. When you bring them proposals, include what you considered and why you’re recommending one path over others.

Mirror their structure when you present to them. Not because you’re mimicking them, but because they’ve revealed what makes sense to their brain.

Risk Orientation

Risk Tolerance: Risk-averse ↔ Risk-tolerant

The question: How comfortable is your manager with uncertainty and risk?

Risk-tolerant managers are willing to experiment and fail fast. They say things like “let’s just try it and see what happens” and “worst case, we learn something.” They’re comfortable with 70% confidence. They’d rather move quickly and course-correct than wait for perfect information.

Risk-averse managers need high confidence before moving forward. They want to see proof, precedent, or exhaustive analysis. They ask “what could go wrong?” and “how do we know this will work?” They’d rather move slowly and get it right than rush and create problems.

Critical nuance: Risk tolerance often varies by domain.

Your manager might be:

Risk-tolerant on product experiments (”let’s test it with 10% of users”)

Risk-averse on people decisions (”I need to be really confident before we make this hire”)

Risk-tolerant on tactical choices (”try it and tell me how it goes”)

Risk-averse on anything that affects other teams or leadership visibility

Map the domains separately. Don’t assume because they’re willing to experiment with features that they’ll be comfortable with organizational changes.

What They Fear Most

Every manager has fears, things that keep them up at night, trigger their anxiety, or make them suddenly rigid in decisions. If you can identify what your manager fears, you can proactively address those concerns and dramatically increase your influence.

Common fears:

Looking bad to leadership - Being unprepared in exec meetings, getting blindsided by questions from their boss

Rework - Shipping something that has to be redone later, wasting team time

Missing commitments - Telling leadership “we’ll deliver X” and then not delivering

Budget overruns - Spending more than planned, especially without warning

Team burnout - Pushing people too hard and losing good people

Competitive threats - Getting outpaced by competitors

Reputational damage - Making decisions that reflect poorly on the team or company

Customer churn - Losing customers due to poor decisions

Loss of trust - Team members feeling blindsided, misled, or micromanaged

How to identify this:

What triggers strong reactions or pushback?

What do they emphasize when they’re stressed?

What stories do they tell about past failures or close calls?

What do they check on repeatedly?

Once you know the fear, proactively address it.

If they fear looking bad to leadership, always give them a heads up before something escalates. Share the “what would our exec ask about this?” analysis with your updates.

If they fear rework, emphasize how you’re validating assumptions early. Show them you’re thinking about sustainability, not just speed.

If they fear team burnout, flag capacity concerns before they become problems. Show them you’re protecting the team.

Zero Tolerance Items (Must Flag Early)

These are the landmines. The things that, if you don’t surface them immediately, will damage trust significantly, sometimes irreparably.

Every manager has them. Your job is to identify them and create a mental alarm system: “If X happens, tell my manager immediately, no matter what.”

Common zero tolerance items:

Timeline slips that affect other teams or external commitments

Budget overruns above a certain threshold

Any customer escalations or complaints

Quality issues that could affect users

Team members showing signs of burnout or dissatisfaction

Decisions that need leadership approval (even if you think it’s minor)

Anything that could create legal, security, or compliance risk

Dependencies on other teams that are at risk

Changes to previously-agreed scope or approach

The pattern to watch for: What has triggered “Why didn’t you tell me about this sooner?!” reactions in the past, either with you or with others on the team?

One bad example can teach you the rule. If your manager ever seemed frustrated or caught off-guard by something you should have flagged earlier, that’s now on your zero tolerance list forever.

The principle: When in doubt, over-communicate on potential landmines. The cost of a false alarm is low. The cost of missing a real issue is high.

Section 3: How They Give & Receive Feedback

This section is about decoding how your manager communicates feedback and builds trust. This is where many people struggle because feedback is often subtle, implicit, or wrapped in politeness. If you can’t read the signals, you’ll be blindsided.

Feedback Pattern: Explicit ↔ Implicit

The question: Does your manager give clear, explicit feedback in words? Or do you need to read body language, tone, and behavior to understand how they really feel?

Explicit feedback managers tell you directly when something’s wrong:

“This isn’t at the quality bar I expected”

“I need you to be more proactive about flagging risks”

“That presentation didn’t land well with the exec team”

With explicit managers, you can take their words at face value. If they say something’s fine, it probably is. If they have concerns, they’ll tell you.

Implicit feedback managers communicate through signals:

They go quiet in meetings when they’re skeptical

They ask a lot of questions when they’re not convinced (the questions ARE the feedback)

Their email response time changes when they’re unhappy

They “table” discussions when they disagree but don’t want confrontation

They give feedback through questions: “Have you thought about...?” instead of “You should...”

Most managers do both, but one dominates.

The critical insight: Most people over-index on explicit feedback. They wait until their manager directly tells them something is wrong before they course-correct.

But your manager has probably been giving you implicit feedback for weeks. You just weren’t reading it.

Signals to watch for (implicit feedback patterns):

Body language:

Leaning back or crossing arms = skeptical

Looking at phone/laptop during your update = not engaged (either bored or the topic isn’t landing)

Leaning forward, making eye contact = interested

Nodding quickly, moving to next topic = they’re with you, move on

Language patterns:

“Interesting...” [long pause] = not convinced

“Help me understand...” = I don’t agree but I’m being polite

“Let’s revisit this” = soft no

“Have you thought about [X]?” = You should have thought about X

Quick “yes, sounds good” = either genuine agreement OR they don’t think it matters enough to engage deeply (context determines which)

Response patterns:

Fast email responses on some topics, slow on others = showing you what they care about

Following up multiple times on the same thing = they’re worried about it

Asking detailed questions = they’re not confident in the approach

Radio silence after you share something = could mean approval (trust), could mean concern (avoiding confrontation)—you need more data points to know which

How to calibrate:

Track patterns over time, not one-off signals

Test hypotheses: “You’ve been asking a lot of questions about the timeline. Are you concerned about our ability to deliver?” (Give them permission to give explicit feedback)

Compare their reactions to different types of updates. What gets a fast “great” vs. what gets lots of follow-up questions?

The most valuable skill: Learning to read your manager’s implicit feedback BEFORE they have to make it explicit. This is how you build trust, they see that you’re paying attention and adjusting without them having to spell everything out.

Quality Bar (What Earns an A+)

The question: What does excellent work look like to your manager?

This isn’t about “work hard” or “be smart.” It’s about understanding the specific elements your manager values in high-quality work.

Different managers have different bars:

Some managers value thoroughness:

Did you think through edge cases?

Did you consider what could go wrong?

Did you validate your assumptions?

Some managers value speed:

How quickly did you move?

Did you ship something or just analyze?

Did you avoid overthinking?

Some managers value proactivity:

Did you identify risks before they became problems?

Did you bring solutions, not just problems?

Did you think ahead to the next question?

Some managers value clarity:

Was your communication crisp?

Did you make a clear recommendation?

Was it easy to understand what you needed?

Some managers value showing your work:

Did you explain your reasoning?

Did you show alternatives you considered?

Did you make tradeoffs explicit?

Here’s the key: You need to know which 2-3 elements matter most to YOUR manager.

How to identify this:

What has earned praise or positive feedback in the past?

What do they emphasize in their own work?

What triggers redos or requests for revisions?

Look at work they’ve forwarded to others or flagged as “this is the standard”

Common A+ elements to watch for:

Clear problem statement

Data/evidence to support the case

Risks identified with mitigation plans

Tradeoffs explicitly stated

Crisp, clear recommendation

Next steps defined

Consideration of stakeholder impact

Showing you thought through implementation

Document what earns an A+ from your manager, then reverse-engineer it into your standard operating procedure.

If your manager consistently praises work that “flags risks early with mitigation plans,” make that a required element of everything you share. Put it at the top of your memos, your updates, your proposals.

Make it easy for your manager to see you’re hitting their quality bar.

Trust-Building Style: Task-based ↔ Relationship-based

The question: What foundation does trust rest on with this manager?

Task-based trust:

Trust is earned and maintained through consistent delivery

It’s transactional: “what have you done lately?”

Personal rapport is nice-to-have, not essential

Trust must be continuously re-earned through performance

They don’t need to like you; they need to rely on you

Relationship-based trust:

Trust requires personal connection first

Once they trust you as a person, they’re more forgiving of occasional missteps

They invest in building rapport (coffee chats, personal questions, getting to know you)

Trust is more durable once established

They need to feel they understand you as a person, not just as a performer

Important note: Everyone starts with some task-based proof. You can’t just befriend your way into a relationship-based manager’s trust without also delivering results.

But this dimension captures what sustains and deepens trust over time.

Task-based managers: You don’t need to grab coffee or chat about weekends. You can have a perfectly professional, somewhat distant relationship, and that’s fine, as long as you deliver. The trust resets frequently. Last quarter’s wins buy you credibility for this quarter, but not much beyond that.

Relationship-based managers: You need to invest time in the relationship, not just the work. They want to understand your motivations, your career goals, how you think. They’ll ask about your weekend, your family, your interests. This isn’t small talk to them, it’s trust-building. Once that foundation is there, they’ll give you the benefit of the doubt when things don’t go perfectly. The trust compounds.

How to identify this:

Do they schedule 1-on-1s that are purely about “how are you?” or is every conversation task-focused?

Do they share personal information about themselves? (This is often a signal they value relationship-building)

When something goes wrong, how do they react? Do task-based managers get transactional (”you need to fix this”), while relationship-based managers first check in on how you’re doing?

Adapt accordingly:

Task-based: Focus on consistent delivery, proactive communication, and demonstrating competence. Don’t take it personally if conversations are brief or strictly professional.

Relationship-based: Invest time in building rapport. Share context about yourself. Ask about them. Take the coffee chat. This isn’t wasted time—it’s infrastructure for the working relationship.

Section 4: How They Operate

This final section captures the practical, day-to-day interaction patterns with your manager. This is the tactical stuff that, when you get it wrong, creates constant friction. When you get it right, everything just flows.

Cadence & Channel

Over-communicate vs. Give Space

The spectrum: Does your manager prefer to be kept in the loop on everything, or do they prefer you handle things independently and only surface what’s essential?

Over-communicate side: These managers want to know what’s happening, even if it’s just FYI. They’ve explicitly said things like “I’d rather you over-communicate than leave me in the dark.” They get anxious when they don’t hear from you. Silence reads as “something might be wrong.”

For these managers:

Default to more updates, not fewer

Use “FYI, no response needed” liberally

Give them visibility even on small decisions

When in doubt, loop them in

Give space side: These managers trust you to handle things. They don’t want constant updates. They’ve said things like “I trust you, just let me know if there’s a problem” or “you don’t need to run everything by me.” Too much communication feels like you don’t have confidence or you’re asking for permission on things you should just decide.

For these managers:

Be selective about what you surface

Focus updates on decisions that need their input or things that could escalate

Default to “I’ll handle it and keep you posted”

When in doubt, make the call and inform them after

How to identify where they fall:

Have they ever said “I wish I’d known about this sooner” or “you don’t need to tell me about every little thing”?

Do they seem relieved or annoyed when you send detailed updates?

How do they manage their other reports? (Watch the patterns)

Critical note: This often shifts based on context. When things are going well, they want space. When there’s a crisis or high-stakes project, they want more communication. Pay attention to the environmental factors.

Preferred Update Rhythm

The question: How often does your manager want to hear from you, and through what channels?

This is about establishing a predictable cadence that prevents both over- and under-communication.

Common patterns:

Daily async updates (Slack, email) for fast-moving projects

Weekly summaries (email, doc) for steady-state work

Bi-weekly 1-on-1s for everything else

Ad-hoc when there’s news (good or bad)

The key is making it predictable. Your manager shouldn’t have to wonder “when am I going to hear about this?” or chase you for updates.

Good pattern: “Every Friday I send a 5-bullet update: wins, blockers, decisions needed, FYIs, what’s next. My manager knows it’s coming. If something urgent comes up mid-week, I flag it immediately, but otherwise everything rolls into Friday.”

Bad pattern: “I update my manager whenever I think of it, which means sometimes they hear from me 3 times a day and sometimes not for a week. They never know if silence means everything’s fine or I’m heads-down and potentially stuck.”

Channels matter too:

Some managers prefer:

Slack/messaging for quick updates and questions

Email for anything that needs a paper trail or involves others

Docs for detailed updates or status reports they can reference later

In-person/video for anything sensitive, complex, or requiring discussion

Watch what channel they use when they reach out to you. That’s often a signal of their preference.

Ask explicitly about cadence early in the relationship: “What’s the best way to keep you updated? Should I send a weekly summary, or would you prefer I just flag things as they come up?”

Time Orientation

Punctuality/Deadline Expectations: Flexible ↔ Strict

The question: How does your manager think about time and deadlines?

Strict time managers:

Commitments are sacred

If you said Friday, they expect Friday

Being late to meetings is noticed (and remembered)

Moving deadlines requires significant justification

“We’ll deliver X by Y” is a contract, not an estimate

Flexible time managers:

Deadlines are guidelines, not hard stops

If there’s a good reason, dates can move

They care more about getting it right than hitting the exact date

Being 10 minutes late to meetings isn’t a big deal

“We’ll deliver around end of Q2” is specific enough

Critical nuance: External vs. internal deadlines

Many managers are:

Strict on external commitments (things promised to customers, leadership, other teams)

Flexible on internal deadlines (team goals, internal milestones)

If you promised something to a customer or your manager committed something to their boss, that date is sacred. But internal team deadlines might have flex if there’s a good reason and you communicate early.

How to identify this:

Have they ever expressed frustration about missed deadlines?

How do they react when you’re late to meetings?

Do they emphasize “on time” or “done right”?

Watch what they do, not just what they say, do THEY hit deadlines strictly?

Adapt accordingly:

Strict managers: Build buffer into estimates. Communicate risks to timelines EARLY. Treat commitments as non-negotiable unless there’s a serious reason to renegotiate.

Flexible managers: Still aim for dates, but focus on communicating clearly about tradeoffs. “We can hit the date with reduced scope, or deliver full scope a week later, what’s your preference?”

Planning Horizon

The question: What timeframes does your manager think in?

Days: Tactical, focused on immediate execution

Weeks/Sprints: Short-term delivery cycles

Months: Mid-range planning

Quarters: Strategic planning cycles

Years: Long-term vision

Why this matters: You need to match your updates to their planning horizon.

If your manager thinks in quarters, don’t give them daily task-level updates in your 1-on-1s. They want to hear about progress against quarterly goals, blockers that could affect the quarter, strategic decisions.

If your manager thinks in weeks, don’t come to them with only high-level strategy. They want to know what’s shipping this week, what’s at risk, what decisions need to be made soon.

Most managers operate at multiple horizons:

Think in quarters for strategy

Think in months for milestones

Think in weeks/sprints for execution

Your job: Figure out which horizon is appropriate for which type of conversation.

1-on-1s: Usually monthly or quarterly progress + immediate blockers

Team meetings: Usually weekly or sprint-level execution

Strategy sessions: Quarterly or annual

Quarterly planning: Annual vision and multi-quarter roadmaps

How to identify their planning horizon:

What timeframe do they reference most in conversations? (”Let’s see where we are by end of quarter” vs. “What’s shipping this sprint?”)

What cadence do they use for goal-setting?

How far out do they want you to think when you’re planning?

What level of detail do they want for different time horizons?

Adapt your communication: If you’re updating on a long-term project, frame it at their horizon: “We’re on track for the Q3 launch. This month we’re focused on the MVP scope. This week we’re finalizing the design.”

Give them the altitude they need, with details available if they want to zoom in.

Authority/Autonomy Style

Management Approach: Hands-on ↔ Hands-off

The question: Does your manager want to be involved in details and decisions, or do they prefer to set direction and let you figure out execution?

Hands-on managers:

Want to be consulted on decisions, even smaller ones

Ask lots of questions about approach and details

Review work before it goes out

Attend meetings you might run without them

Want frequent check-ins

Hands-off managers:

Set direction and expectations, then trust you to execute

Don’t want to be involved in details unless there’s a problem

Review only final outputs or major decisions

Skip meetings where you’re leading

Check in periodically but give you space

Critical insight: This often changes as trust builds.

Many managers start hands-on with new reports or new projects. They’re calibrating, learning your judgment, your quality bar, your communication style. As you prove yourself, they back off.

If your manager is hands-on, don’t interpret it as lack of trust (yet). It might just be their onboarding process. The question is: Does it stay that way, or do they give you more rope over time?

Also: Context matters.

Your manager might be:

Hands-off on routine execution

Hands-on during critical launches or crises

Hands-off on areas where you have expertise

Hands-on on areas that are new to you or politically sensitive

How to identify this:

How much do they want to know about your day-to-day decisions?

Do they want to review work-in-progress or just final outputs?

When you propose something, do they approve quickly or dig into details?

Watch how they manage others on the team

Adapt accordingly:

Hands-on: Give them the visibility they need. Don’t take it personally. Proactively share work-in-progress. Ask “do you want to review this before I send it?” Build trust by showing them your thinking, not just your outputs.

Hands-off: Don’t ask for permission on things you should just decide. Update them on outcomes, not every step. When you do need their input, be explicit: “I need your decision on X” vs. “FYI, here’s what I’m doing.”

What They Want to Be Consulted On

This is where you define the boundaries of your autonomy.

The goal: Create a clear, shared understanding of:

What decisions you bring to them

What decisions you make independently

What you just keep them informed about

Common categories managers want to be consulted on:

Customer-facing decisions:

Anything users will see or experience

Communications going to customers

Pricing or product changes

Feature prioritization that affects customer promises

Budget/Resource decisions:

Spending above a certain threshold (often $X or 10% of budget)

Hiring decisions

Vendor selection

Allocation of team time or resources

Precedent-setting decisions:

First time doing something that could become a pattern

Process changes that affect how the team works

Decisions other teams might want to reference or copy

Cross-functional decisions:

Anything that affects other teams

Dependencies you’re creating

Commitments you’re making on behalf of the team

High-risk decisions:

Anything that could escalate to leadership

Decisions that are hard to reverse

Technical architecture choices with long-term implications

Things requiring leadership approval:

Even if you think it’s minor, if it might need their boss’s buy-in, flag it

Changes to previously-agreed scope, timelines, or goals

Your job: Build this list explicitly with your manager.

In an early 1-on-1: “I want to make sure I’m bringing you the right things and not bothering you with decisions I should just make. What types of decisions do you want me to consult you on vs. just keep you informed?”

Then test the boundaries.

“I’m planning to [X]. Based on our conversation, I think this is in the ‘decide and inform’ bucket, but wanted to double-check. Does that sound right?”

Over time, the list should shift. As trust builds, more things move from “consult” to “inform.”

What I Can Decide & Inform

The flip side: What are you empowered to decide independently?

Common categories for independent decision-making:

Tactical execution choices:

How you approach the work

Tools and methods you use

Sequence of tasks

Day-to-day problem-solving

Internal processes:

How you organize your own work

Templates or workflows you use

Communication approaches within the team

Day-to-day prioritization:

How you sequence your own tasks

What you work on this week vs. next

Which bugs to fix first (within agreed priorities)

Task assignments:

Who does what on your projects (if you’re leading)

How you distribute work within agreed scope

The principle: If the decision is:

Easily reversible

Low stakes (won’t escalate, won’t set precedent, won’t affect others significantly)

Within your area of ownership

Doesn’t require budget/resources beyond what’s already allocated

Then you should probably just decide and inform.

Document your boundaries clearly. Keep a running list:

Consult first:

[Specific examples from your context]

Decide and inform:

[Specific examples from your context]

When in doubt:

If it’s your first time deciding something like this, consult

If it feels like it could escalate, consult

If your gut says “I should probably mention this,” consult

Better to over-consult early and build trust than to make a decision that should have been escalated.

As your model gets better, you’ll develop instinct for where the boundaries are.

Putting It All Together: Your Living Model

Here’s what makes this powerful: This isn’t a one-time exercise.

Your predictive model is a living document that you continuously refine based on new observations. Think of it like a mental API for working with your manager, and like any good API, it needs maintenance and updates.

Notes & Pattern Updates

Recent Observations

This section is your observational journal.

Capture patterns as you notice them:

“10/15: Noticed she’s been more stressed lately - asking more questions, wants more frequent updates. Probably pressure from above. Adjusting to over-communicate more for now.”

“11/3: He was much more hands-off this week after the successful launch. Seems like his involvement increases with risk/uncertainty, then backs off when things are stable.”

“12/8: Realized he always asks ‘what’s the customer impact?’ first when I bring product ideas, but asks ‘what’s the effort?’ first when I bring technical improvements. Different decision framework for different types of work.”

“1/20: She gave implicit feedback in the meeting - went quiet and started checking her phone when I was explaining the technical approach. Need to lead with business impact, not technical details.”

What to track:

Changes in behavior (often driven by external pressure you can’t see)

Patterns that emerge over multiple interactions

Anomalies that don’t fit your current model

Context-dependent variations (how they act in different situations)

This isn’t about obsessing over every interaction. It’s about being intentionally observant and capturing insights when they emerge.

Frequency: Add notes after significant interactions or when you notice something new.

Don’t wait for the annual review to realize “oh, I’ve been doing this wrong for months.” Capture patterns in real-time.

Predictions I Tested

This is where your model gets sharper.

The practice: Before sending an important update or making a significant request, pause and predict:

“Based on my model, I think my manager will:

Ask about [X]

Want to see [Y]

Be concerned about [Z]”

Then send it and compare your prediction to reality.

Examples:

Prediction: “I’m proposing a 3-month project. Based on her optimization for speed and risk-aversion on team capacity, I predict she’ll ask: (1) Can we do a faster MVP version? (2) Do we have the team bandwidth for this?”

Reality: ✅ She asked both questions in the first 5 minutes. Prediction accurate. Model confirmed.

Prediction: “I’m flagging a timeline slip. Based on his zero-tolerance for surprises to leadership, I predict he’ll want to know immediately and will ask what our recovery plan is.”

Reality: ✅ He thanked me for the early heads-up and asked for the mitigation plan. Then he said “let me know if you need help communicating this upward.” Prediction accurate + learned he wants to help with stakeholder management on issues.

Prediction: “I’m sending a detailed analysis. Based on her preference for bottom-line-first and low detail tolerance, I predict she’ll skim it and just want the summary.”

Reality: ❌ She actually read the whole thing and asked detailed follow-up questions. Learned: She wants high-level for routine updates, but goes deep on strategic decisions. Need to refine model - detail tolerance varies by decision type, not uniform.

This is the feedback loop that makes your model accurate.

You’re not just observing passively. You’re actively testing hypotheses about how your manager operates, then updating your model based on what you learn.

Over time, your predictions get scary good.

You can anticipate:

What questions they’ll ask before they ask them

What will trigger pushback before you propose it

What information they’ll need before they ask for it

When to loop them in vs. when to just decide

This is what separates good operators from great ones. Great operators have accurate predictive models. They make their manager’s life easier because they’re consistently in sync.

How to Build Your Model: The Process

If you’re starting from scratch, here’s the systematic approach:

Week 1-2: Observation Mode

Start documenting everything. After every interaction with your manager:

What did they ask about?

What did they emphasize?

What seemed to land well?

What triggered questions or pushback?

How did they communicate (explicit or implicit feedback)?

Don’t try to act on patterns yet. Just collect data.

Week 3-4: Pattern Recognition

Review your notes. Look for recurring themes:

What questions do they ask repeatedly?

What communication style do they use consistently?

What types of updates get fast responses vs. slow responses?

When do they lean in vs. check out?

Start forming hypotheses: “I think my manager optimizes for speed over perfection” or “I think my manager needs high context before making decisions.”

Week 5-6: Testing Predictions

Start deliberately testing your hypotheses:

“Based on my observation, I think they’ll want to see data first. Let me lead with numbers and see how it lands.”

“I think they prefer bottom-line-first. Let me structure my update that way and see if it flows better.”

Compare predictions to reality. Refine your model based on what you learn.

Week 7-8: Adaptation

Start consistently applying what you’ve learned:

Adjust how you structure updates

Proactively address their recurring questions

Match their preferred communication style

Flag things early based on their zero-tolerance items

Notice: Does communication get smoother? Do you get fewer follow-up questions? Does your manager seem less stressed when interacting with you?

Ongoing: Maintenance

Your model needs continuous updates:

Monthly: Review your notes. What patterns emerged this month?

Quarterly: Step back and assess. Has anything shifted? Are there new patterns?

After significant events: Launches, re-orgs, stressful periods—these can change behavior. Update your model.

The model is never “done.” Your manager evolves. The context changes. Your relationship matures. Keep observing. Keep refining.

Why This Works: The Compounding Benefits

Let’s talk about what happens when you consistently apply your predictive model.

1. You Build Trust Faster

When you consistently give your manager what they need, in the way they need it, without them having to ask, they start trusting your judgment.

They think: “This person really gets it. They understand how I think. I don’t have to micromanage them.”

Trust compounds. Each successful prediction, each time you proactively address their concern, each time you communicate at the right level of detail, each time you flag risks early, adds a brick to the foundation.

The outcome: More autonomy. Your manager gives you bigger projects, more independence, more latitude to make decisions.

2. You Reduce Friction

Without a predictive model, every interaction has friction:

You send too much detail, they get frustrated

You send too little, they have follow-up questions

You structure updates in a way that doesn’t land

You miss signals that they’re unhappy

With a model, communication becomes smooth.

You’re speaking their language. You’re addressing their concerns before they voice them. You’re showing them information in a format that makes sense to their brain.

The outcome: Less time wasted on back-and-forth. Fewer misunderstandings. More efficient collaboration.

3. You Get Better at Influencing Outcomes

When you understand:

What your manager optimizes for

What evidence they find compelling

What their fears are

How they make decisions

You can design proposals that land.

You’re not hoping they’ll agree. You’re deliberately framing your recommendations in a way that addresses their decision drivers, provides the evidence they need, and mitigates the risks they care about.

The outcome: Higher success rate on getting buy-in. More of your ideas get traction. You become more effective at driving change.

4. You Avoid Blindsides

Remember: most managers give lots of implicit feedback long before they give explicit feedback.

When you’re good at reading signals, you can course-correct before there’s a problem.

You notice:

They’re asking more questions than usual → they’re not confident in the approach → adjust before they lose faith

They’re responding slowly to updates → something’s not landing → check in proactively

They’re using different language → their priorities have shifted → realign your focus

The outcome: Fewer performance review surprises. No “I didn’t know this was an issue” conversations. You’re addressing concerns in real-time.

5. You Earn Space to Operate

This is the ultimate unlock.

When your predictive model is accurate, your manager gives you more freedom.

Why? Because you’ve proven:

You understand their constraints

You make decisions they would make

You flag things they care about

You communicate in ways that work for them

They don’t need to be hands-on because you’re an extension of their judgment.

The outcome: You get to work on more interesting problems. You have more authority. You spend less time asking for permission and more time executing.

The Meta-Skill: Observation Over Assumption

Here’s the fundamental mindset shift this entire framework requires:

Stop assuming. Start observing.

Most people approach managing up with assumptions:

“My manager probably wants X”

“I think they care about Y”

“They seem like a Z type of person”

These assumptions are often wrong. And when they’re wrong, you waste time and political capital.

The predictive model approach says:

Don’t assume, observe

Don’t hope, test

Don’t guess, document

Every manager is different. The things that worked with your last manager might not work with this one. The advice you read in a blog post might not apply to your specific situation.

Your job is to become a student of your specific manager.

Watch how they operate. Track patterns. Form hypotheses. Test them. Update your model based on what you learn.

This is a skill that compounds across your entire career.

Once you know how to build a predictive model for one manager, you can do it for any manager. You can do it for stakeholders, exec sponsors, cross-functional partners.

The observation muscle gets stronger the more you use it.

You get faster at pattern recognition. You get better at reading implicit feedback. You develop instinct for what matters.

And here’s the beautiful irony:

When you stop trying to change your manager and instead adapt to how they actually operate, you often end up having more influence.

Because you’re working with reality, not fighting against it.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

As you build your model, watch out for these traps:

Pitfall 1: Building a Model Based on What You Wish Were True

The trap: You want your manager to be data-driven, so you keep bringing them data, even though they consistently respond better to stories.

The fix: Your model must be based on observed behavior, not your preferences or assumptions about what “good management” looks like.

If your manager is relationship-based and you wish they were task-based, too bad. That’s not reality. Build your model around reality.

Pitfall 2: Over-Indexing on One Data Point

The trap: Your manager asked for more detail once, so now you assume they always want detail.

The fix: Look for patterns across multiple interactions. One data point could be an anomaly. Three similar data points is a pattern. Ten is a strong signal.

Pitfall 3: Assuming Your Model Is Static

The trap: You figured out your manager six months ago, and you haven’t updated your model since.

The fix: People change. Context changes. Your relationship matures. Keep observing. Keep updating.

Your manager might become more hands-off as you build trust. They might become more risk-averse when the company hits a rough patch. Your model needs to evolve.

Pitfall 4: Using the Model to Avoid Difficult Conversations

The trap: “My manager hates conflict, so I’ll just never disagree with them.”

The fix: The model is about understanding how to communicate effectively, not about avoiding necessary conversations.

If your manager is conflict-averse, that doesn’t mean you never push back. It means you do it thoughtfully, in private, with data, framed as “help me understand” rather than “you’re wrong.”

Pitfall 5: Forgetting That Adaptation Goes Both Ways

The trap: You adapt entirely to your manager and lose your own voice or judgment.

The fix: The goal isn’t to become a mirror of your manager. It’s to understand them well enough to collaborate effectively while maintaining your own perspective.

You adapt your communication style and approach. But you don’t compromise your values or stop thinking independently.

Good managers actually want people who can think differently from them—as long as those people can communicate in a way that lands.

Getting Started: Your First Steps

If you’re reading this and thinking “okay, I’m in—what do I do now?”

Here’s your action plan:

Step 1: Start Your Observation Log

Create a simple doc (Notion, Google Doc, wherever you keep work notes). Title it “Manager Working Style” or “Predictive Model” or whatever works for you.

After your next few interactions with your manager, spend 5 minutes capturing:

What did they ask about?

What did they seem to care about?

How did they communicate?

What landed well? What didn’t?

Do this for 2 weeks. Just observe and document. Don’t try to act on patterns yet.

Step 2: Use the Framework as Your Scaffold

After 2 weeks of observation, open up the worksheet (the one we built in this post). Start filling it in based on what you’ve observed.

You won’t have answers for everything yet. That’s fine. Mark where you have strong signals, where you have hypotheses, and where you have no data yet.

Step 3: Test One Prediction

Pick one element from your model. Maybe it’s:

“I think my manager wants bottom-line-first communication”

“I think my manager needs context before diving into details”

“I think my manager cares most about customer impact”

Before your next significant interaction, make a prediction based on that element. Then see what happens.

Did your prediction hold? Great, you’ve confirmed that part of your model.

Did it not hold? Even better, you’ve learned something. Update your model.

Step 4: Make One Adaptation

Based on what you’re learning, adjust ONE thing about how you interact with your manager.

Maybe you:

Start sending a weekly summary instead of ad-hoc updates

Lead with data instead of stories (or vice versa)

Flag potential risks earlier

Provide more context before getting to recommendations

Pick one adaptation. Try it for 2-3 weeks. Notice if things get smoother.

Step 5: Keep Refining

Make this part of your routine:

After important interactions, capture observations

Monthly, review patterns

Continuously test and update predictions

Over time, this becomes second nature.

You’ll stop thinking “I need to check my model” and start just intuitively knowing how to work with your manager effectively.

The Bigger Picture: This Is About Agency

Here’s what this framework is really about:

Taking ownership of the relationship.

Most people wait for their manager to tell them how to work together. They wait for their manager to change. They wait for things to magically get better.

Building a predictive model is about recognizing: You have agency here.

You can’t control your manager’s personality or preferences. But you can control:

How you observe and learn

How you adapt your communication

How you show up in the relationship

This is empowering.

Instead of feeling frustrated that your manager “just doesn’t get it,” you can step back and ask: “What am I missing? What pattern haven’t I noticed? How can I adjust my approach?”

Some people will read this and think it’s about being accommodating or subservient.

It’s not.

It’s about being strategic. It’s about recognizing that understanding the system you’re operating in makes you more effective. It’s about adapting your communication to be heard, not changing who you are.

The best operators do this instinctively.

They’re not just good at their jobs. They’re good at working with their managers. They make their manager’s life easier, which in turn makes their own life easier.

They earn trust faster. They get more autonomy. They drive more impact.

And it all starts with observation.

Final Thoughts

Your manager is a complex system. They have patterns, preferences, fears, and quirks; just like you do.

Most people never bother to really understand that system. They work on their craft, they focus on their tasks, and they wonder why they’re not getting the recognition or autonomy they want.

Building a predictive model changes that.

It shifts you from reactive (”why is my manager frustrated?”) to proactive (”I know exactly what my manager needs, and I’m going to provide it before they ask”).

It transforms your relationship from transactional to strategic.

And it gives you a superpower that compounds throughout your career: the ability to quickly understand and effectively work with any manager, stakeholder, or leader.

Start small. Start now.

Open a doc. After your next interaction with your manager, write down three observations.

Then do it again.

And again.

Patterns will emerge. Your model will form. Your working relationship will improve.

And six months from now, you’ll look back and realize: this was one of the highest-leverage skills you ever developed.

Your turn:

Open that doc. Title it “Manager Predictive Model.” And start observing.

What’s one pattern you’ve already noticed about how your manager operates? Write it down. That’s your first data point.

Now go collect more.

-Rinaldo

P.S. - Here is how I can help you move your ideas forward:

1. Company Workshops, Keynotes & Leadership Training:

Help your team communicate with clarity, present with confidence, and turn insights into action. Whether it’s a keynote, offsite, or manager training, I’ll equip your team with storytelling tools they can use immediately.

-> Share your details here and I’ll reach out to explore what fits.

2. Join the Beta: Live Cohort Course (Limited Spots)

I’m launching a hands-on program to help leaders and ICs master strategic storytelling. Specifically, how to guide stakeholders through strategic questions instead of presenting at them. So your ideas don’t just get heard, they get acted on and you get confident buy-in without defending yourself or needing a louder voice. Think: frameworks, live feedback, and real transformation in how you show up.

-> This is the beta round, so spots are limited, discounted, and the experience will be highly personalized. Leave your info here if you’re interested and I’ll send details soon.

Thank you for your encouragement! I credit my client for asking about how she could have a better relationship with her manager. That takes humility and then courage to try something new. I'm sure she'll get a lot out of the article. You've done a great job.

Very interesting article! Several months ago, I was working with a client who asked me this exact question: "No matter what type of information I give her, my manager always seems unhappy...how can I improve our relationship?"

We walked through a few scenarios and identified her manager's patterns. Turned out her manager wanted a plan to make progress, but my client was always presenting background details and thinking that they would discuss a plan together.

It also turned out that she wanted a relationship, but her manager was very task-focused. Once we talked through these differences and made a game plan to approach the manager differently, everything changed. Things are much better in the office now.

I plan to forward this article to her to see if there's anything else in it that catches her eye. Thank you for discussing this very interesting concept.